| |

Classic Astrophotos, Episode Two

11/21/2021. When I posted this picture in the Howling at the Moon section, I asked when people began shooting lunar eclipses this way. That led to a small quest, like the one last March surrounding my recreation of John Stofan's classic photo of Orion setting.

In principle, it's simple: as the Moon orbits through the shadow of the Earth, its surface forms a moving screen upon which different parts of the Earth's shadow land. Photograph the Moon a few times during its passage through the shadow, align the images against the stars, adjust for parallax, and voila! a large part of the Earth's shadow becomes clearly visible.

1/8, 1/4, 1/8 seconds plus 1 second for the starfield

Click the pic to see it way better.

These "Shadow of the Earth" photos became something of a cliche some years ago. I may not have found the earliest examples, but I've found a few that likely inspired generations of astrophotographers who continue to riff on the theme.

It used to be harder than it is now. Now you shoot a gazillion photos and pick those spaced to your liking, adjust the exposures to show what you want to show. Pull them into Photoshop layers, line up the stars, tweak the Moon a bit (shooting from a nearby, rotating planet introduces some parallax, the inverse of the observer's apparent motion as seen from the Moon; the Moon shifts owing to parallax, the shadow does not, or at least it shifts differently), and blend the images to taste for clarity, color, and emphasis. It hasn't always been like that.

To find the progenitors and trend-setters of these images, I looked through Sky and Telescope magazine for stories containing the phrase "lunar eclipse." It's possible that I missed a few pieces that covered such events without using the exact phrase, and there might be some examples from earlier decades.

Apparently measuring the size of the Earth's shadow by accurately timing when craters entered and exited the umbra was quite the project in the 40's, 50's, 60's and some of the 70's. In the absence of satellite monitoring and extensive high-altitude wx sensing, that data was apparently of interest in atmospheric science because it said something about the transparency and relative density of the upper air. There's overlap in the literature between the enthusiasm for crater timing and the advent of "shadow of the Earth" photos.

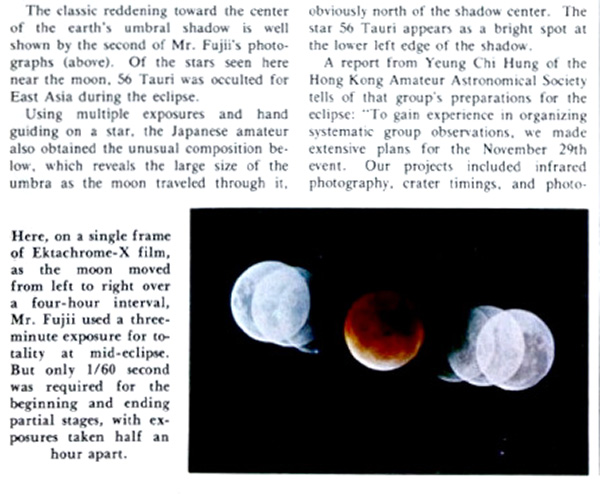

The photos began with Akira Fujii and another eclipse among the bright star clusters of Taurus in 1974.

Akira Fujii is a name among amateur astronomers; he's one of our elders. [ETA, 2022: was one of our elders.] On November 29, 1974, he made multiple exposures of a lunar eclipse near the Hyades on a single frame of color slide film. While the caption explains some of the details, it leaves unsaid that if he screwed up an exposure, or the timing, or bumped the camera, the telescope, or the mount, it was all over. I'm guessing he experimented at previous full Moons to determine the approximate exposure to produce graceful combinations of the partial phases and relied on experience for his one and only chance to photograph mid-totality.

Sky & Telescope, March 1975, p 191.

Photo by Akira Fujii

Note the lead time. If that issue of S&T hit newsstands and subscribers' mailboxes in late February, then something like ninety days elapsed between pushing the button and putting the result before the public. (My neighbors posted their photos of "my" eclipse on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter while my cameras were still gathering frost and photons.)

Shortly after Fujii's image made the rounds, Wolfgang Palzer photographed an eclipse on November 18, 1975. It was within a few degrees of the same sky location as the 2021 eclipse. Herr Palzer used black and white film, made multiple exposures, and aligned them in the darkroom. Modern times, eh? Here's the photo he sent to S&T.

Sky & Telescope, February 1976, p 78.

Photo by Wolfgang Palzer

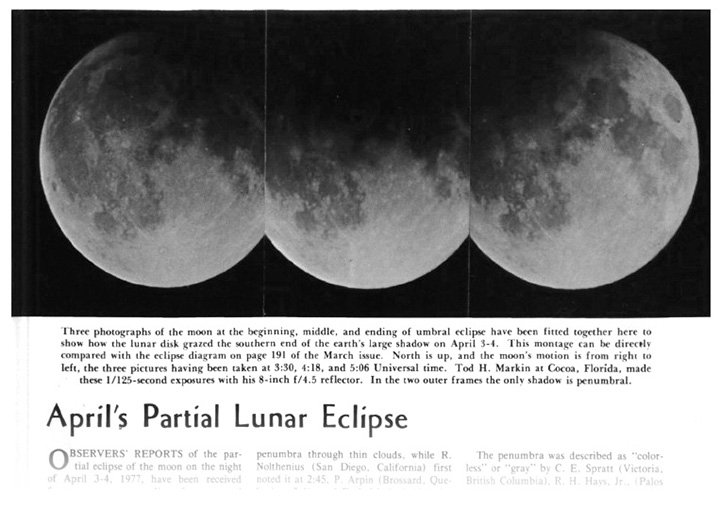

Tod Markin's work appeared in the magazine at least four times during the mid-1970's. To photograph a partial eclipse in Virgo, he used an 8-inch telescope and black and white film. The lunar eclipse of April 3, 1977, was about as shallow as "mine" was deep. The Earth totally eclipsed the Sun only from locations near the Moon's north pole; in the left and right images, no part of the Moon is completely shaded. Still, the general shape and size of the Earth's shadow is made plain in this photo from the June 1977 issue.

Sky & Telescope, June 1977, p 423.

Photo by Tod H. Markin

Tod printed the individual frames, cut the prints carefully, and pasted them together to form this mosaic.

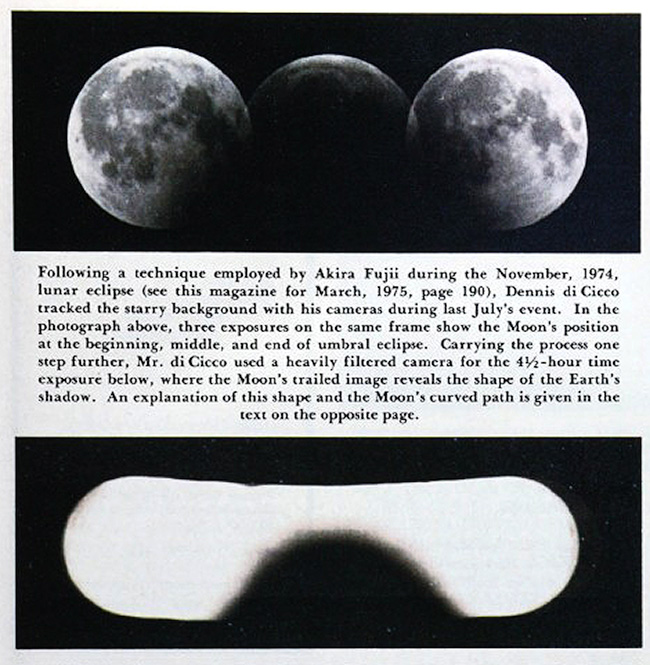

During the 1980's there were more examples. In October 1981, Dennis di Cicco published two. One was a tryptich shot on a single frame. The accompanying text credited Akira Fujii for the idea and technique and cited his 1974 effort. The other was an innovative, long exposure (4.5 hours) tracked on the stars during which the Moon trailed through the shadow:

Sky & Telescope,October 1981, p 392.

Photos by Dennis di Cicco

The text mentioned in the caption explains (as I finally figured out) that the curved path of the Moon is due to parallax from the motion of the observer on the rotating Earth. It also explains why the shadow is oddly shaped in the streak photo. Penumbral shading against a trailed circular screen exacerbated by the different albedos of lunar seas and highlands combines to render brightnesses that differ from the true levels of illumination within the shadow.

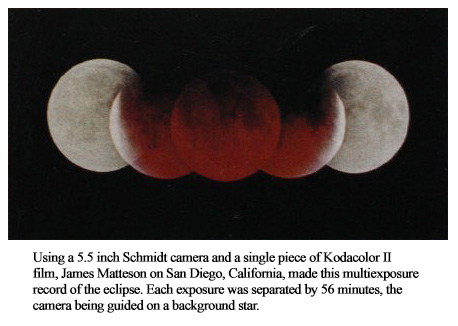

One year later, in October 1982, S&T published a beautiful five-exposure example captured by James Matteson:

Sky & Telescope, October 1982, p 393.

Photo by James Matteson

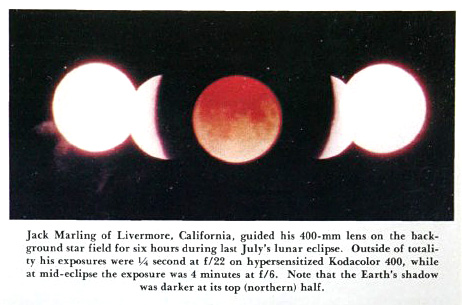

Jack Marling photographed the Earth's shadow during a long total eclipse on July 5-6, 1982, which Sky & Telescope published in December 1982. He made multiple exposures on a frame of color negative film, Kodacolor 400, which he had baked in hydrogen-rich gas in order to "hypersensitize" it. We did things like that back in the day, before solid-state detectors. Jack Marling was the owner and founder of Lumicon, a company that served astrophotographers for many years with filters, guiders, all sorts of specialized gear, and many varieties of "hypered" film stock. Hypersensitized or not, look at those exposures! Four minutes at F6 at mid-totality.

Sky & Telescope, December 1982, p 618.

Photo by Jack Marling

When S&T needed a photo like this for an article in their August 1989 issue, they pulled Jack's seven-year-old effort from the morgue and resurrected it. (It was, of course, a complete coincidence that Jack's company routinely ran full-page ads in the magazine, including a two-page spread in that issue.)

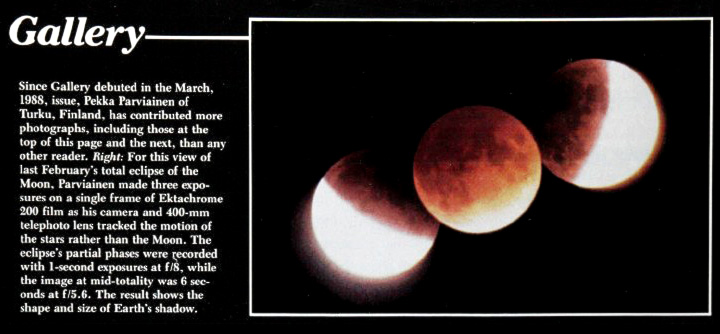

In July 1990, Sky & Telescope's "Gallery" section featured Pekka Parviainen's version which followed the by-then-standard recipe of capturing multiple exposures on a single frame of film while the telescope tracked the stars:

Sky & Telescope, July 1990, p 109.

Photo by Pekka Parviainen.

I'm still looking for the first digital rendition and for additional examples from the 1990's and early 2000's.

The searchable archives of NASA's Astronomy Picture of the Day contain many (excellent) modern examples of these photos going back to the year 2000. including this one

in which Igor Vin'yamimov composited images from five eclipses (September 1997, May 2004, September 2006, August 2008, and June 2011 to show the entire shadow of the Earth.

When we do pictures like these, maybe we're being derivative, or maybe we're paying homage to our predecessors. They're fun.

:: top ::

My deep-sky photos are made with a variety of sensors and optics. Deepest images come now from a ZWO ASI1600MM Cooled Pro CMOS camera, an ASIair (model 1) and sometimes one of several laptops. A good many images come from an unmodded Canon 6D but a lot more will be coming from an R6. Video and video extracts begin in a Canon EOS M, usually running in crop mode via Magic Lantern firmware (but the 6D and especially the R6 will probably see more use). Telescopes include an AT10RC, an Orion 10" F4 Newtonian, and a pair of apochromats: a TMB92SS and a AT65EDQ. A very early Astro-Physics 5" F6 gets some use, too. So do lots of camera lenses on both the ASI1600 and on the Canons. A solar Frankenscope made using a 90mm F10 Orion achromat and the etalon, relay optics, and focuser from a Lunt 60 feeding a small ZWO camera will see more action as the Sun comes back to life (Autostakkart!3 is my current fav for image stacking). Mounts include an iOpton SkyTracker (original model), a bargain LXD-55, a Losmandy G11 (492 Digital Drive), and an Astro-Physics Mach1. PixInsight does most of the heavy lifting; Photoshop polishes. Some of the toys are more or less permanently based in New Mexico. I desperately hope to get back soon.

|